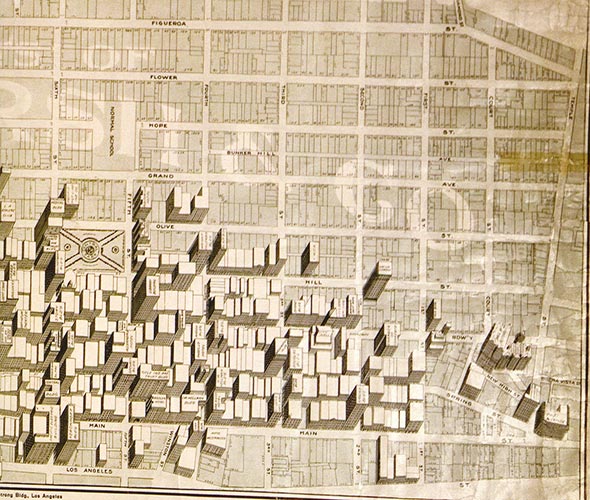

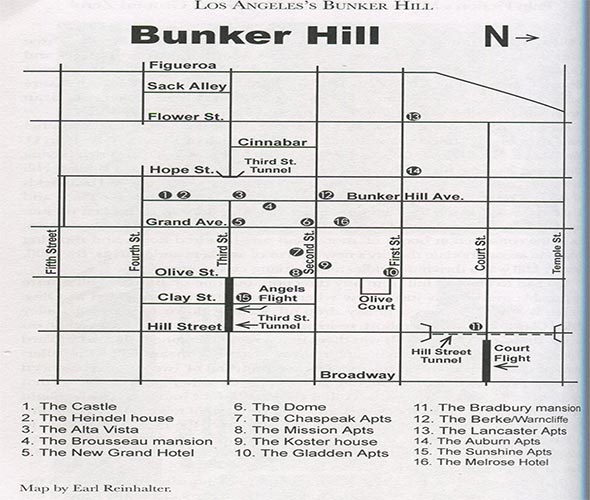

Bunker Hill was formerly bounded by Temple Street to the north, The Los Angeles Normal School (the predecessor to UCLA) to the south, Hill Street to the east and Flower Street to the west. Named in 1875 for the 100th anniversary of a Revolutionary War battle in Boston. This district included streets such as Bunker Hill Avenue, Clay Street, and Court Street which no longer exist.

Builder, Prudent Beaudry (Beaudry Street presently runs east of the 110 Freeway) purchased the Bunker Hill area for $517 in 1867, and first developed the hill in 1869.

Although the land offered a premonitory view of the developing city it lacked a water or sewer system. Beaudry set up his own water and sewer system, made roads, landscaped the area, and connected the 20 acres to the rest of Los Angeles. Initially the residences on Bunker Hill were modest. Beaudry took up residence at 147 North Hill Street with a not so modest home. By the 1880s Bunker Hill was home to the most prominent Los Angeles families.

The Bradbury mansion was built in 1887, and has since become a symbol of Los Angeles’ failure to preserve its architectural history.

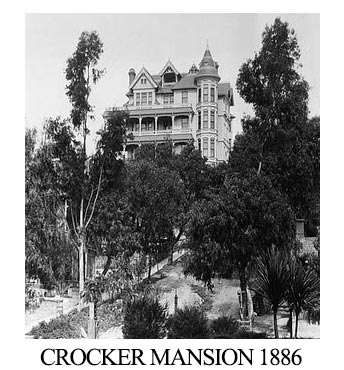

Los Angeles magnates on Bunker Hill included the widow of Supreme Court Justice Crocker whose brother was the railroader, and Van Nuys (a Syndicate member who developed Tract 1000 aka the San Fernando Valley and in 1911 held the largest land auction in history). The Crocker mansion located at 300 South Olive was destroyed to make the Third Street Tunnel at Hill Street.

VAN NUYS MANSION AS IT LOOKED IN 1904

Homes on Bunker Hill were Queen Anne Victorians. These gingerbread residences were often three story ornate residences with the most up-do-date modern conveniences. Barristers left on their tails when they came home for hot lunches, served by servants. Fashionable ladies held court on pre-planned days of the week. If the invited, mannered, Mrs. could not attend she would send a servant to bring a gift and leave her Mrs.’s calling card. Victorian gardens dotted the hills, often with native California plants. Bunker Hill was the most elite section of Los Angeles through the turn-of-the Twentieth Century.

As Los Angeles moved westward towards Mid-Wilshire, Los Feliz, and Beverly Hills, the elegant mansions on Bunker Hill turned into rooming houses. Boarding house became a leading symbol in Los Angeles film noir. The rooming house, like Bunker Hill, was merely a place to pass time before moral and physical decay overtook the person.

Decaying Bunker Hill of the late 1930s was described in Chandler’s short story The King in Yellow:

Court Street was old town, wop town, crook town, arty town. It lay across the top of Bunker Hill and you find anything from down-at-heels ex-Greenwich-villagers to crooks on the lam, from ladies of anybody’s evening to County Relief clients brawling with haggard landladies in grand old houses with scrolled porches, parquetry floors, an immense sweeping banister of white oak, mahogany and Circassian walnut.

It had been a nice place once, had Bunker Hill, and from the days of its niceness there still remained the funny little funicular railway, called the Angel’s Flight, which crawled up and down a yellow clay bank from Hill Street.

In 1934 John Fante roomed at the Alta Vista, located at 225 South Bunker Hill. In his 1939 novel, Ask The Dusk, wrote about his stay at the Alta Vista when speaking from his alter ego Arturo Bandini, and immortalized Los Angeles for which it has always been even if the homelands of its denizens have changed:

Up the dusty stairs of Bunker Hill, past the soot-covered frame building along that dark street…Dust and old building and old people sitting at windows, old people tottering out of doors, old people moving painfully along the dark street. The old folks from Indiana and Iowa and Illinois, from Boston and Kansas City and Des Moines, they sold their homes and their stores, and they came here by train and by automobile to the land of sunshine, to die in the sun, with just enough money to live until the sun killed them…With their bright polo shirts and sunglasses, they were in paradise, they belonged.

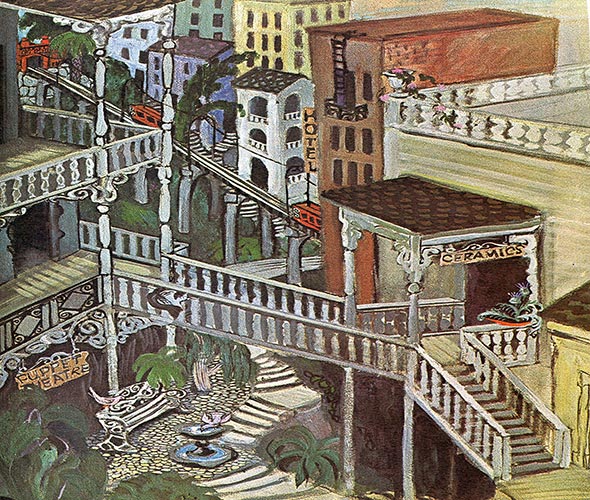

From Leo Politi published watercolors

he painted during Bunker Hill’s final days. Karl Gerber, Private Collection

Jack Webb grew up at the St. Regis Apartments on 237 South Flower, playing in the garbage, before being given the green light by Chief Parker to write and direct the ultimate Los Angeles noir radio show and television program, Dragnet and a number of film crime noirs in the 1950s.

The Artist’s Colony, in its more decrepit state, appeared in many film noirs at the beginnings or ends of the line.

During the early 1960s Bunker Hill was bulldozed and leveled. A new Los Angeles was underway.

A few random building were moved from Bunker Hill to Heritage Square off the 110 Freeway in the Montecito Heights area.

In 1965 445 South Figueroa was the first completed high-rise where Los Angeles’ early elites once bunked in single-family hilltop mansions.

Today, instead of Bunker Hill we have some of the world’s most unfriendly streets and creations of mass such as Flower Street which is partially underground, 333 South Hope (an office tower accessible through a secret streets and paths), 633 West Fifth (the tallest building in Los Angeles with an awful parking garbage of limited egress, accessible from a hidden street behind it), the Omni Hotel which is partially hidden underneath a raised street, California Plaza which is so massive it is difficult to walk its perimeter or find its door, and every other office tower serving downtown’s big business and legal community.

THESE STEPS HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH BUNKER HILL DESPITE BEING CALLED, “BUNKER HILL STEPS.” THIS FIVE-STORY, 103 STEP CLIMB, WAS BUILT in 1990 BY MAGUIRE PARTNERS, A HIGH RISE LANDLORD IN DOWNTOWN, AS PART OF A BROKERED DEAL FOR THEM TO BREAK A HEIGHT LIMIT AND BUILD THE MONSTROSITY CALLED, “US BANK BUILDING” WHICH REQUIRES A SECOND ELEVATOR AT THE 54TH FLOOR JUST TO GET TO FLOORS 55 THROUGH 72.

Important books on Bunker Hill include Jim Dawson’s Los Angeles’s Bunker Hill and Leo Politi’s Bunker Hill Los Angeles.

Since writing this article sometime ago, it is essential that Los Angeles Before the Freeways be added to must haves about Bunker Hill. Arnold Hylen photographed Bunker Hill in its final days much like Leo Politi water colored it. Nathan Marsak recently acquired the rights to the photographs and republished them in this book. Upon opening the book, it was clear that it contained the largest number of photographs of what once was. Flipping through the pages and reading about how the hotel where Isaias Hellman got married was razed, the second oldest building in Los Angeles (1835) was destroyed for unknown reasons, blocks built by those who made Los Angeles 20-40 years before 1900 brought not joy in finally seeing these photographs, but indignation. Sadly, this was a city those of who were born after the mid-1950s, or came here thereafter, never had the pleasure to know. Blocks built to the highest standards by our city founders were repeatedly razed to plop down parking lots and non-descript commercial buildings. Although this was always known, picture after picture presented a final reckoning intentionally neglected by Los Angeles historians because the truth was too brutal to face.

Because Mr. Marsak paid dearly for the rights to Hylen's photographs they will not be re-published here. Instead, you are invited to view a video somebody who worked for the Employment Lawyers Group, at the time, put together based upon a segment Karl Gerber did about Bunker Hill on KABC radio in Los Angeles. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pwH61SkKFlw

Comments